MY JOURNEY IN JAKANDE’S “SCHOOL OF JOURNALISM” BY FOLU OLAMITI

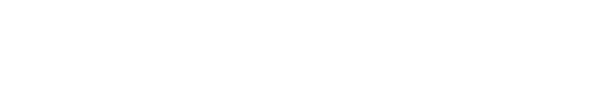

This page is supported by Shell Nigeria. Click here for more information

By Folu Olamiti FNGE

GREATRIBUNETVNEWS–A lot has been said and written about the late elder statesman, Alhaji Lateef Kayode Jakande, popularly known as LKJ, who passed on to the world beyond and was laid to rest recently He was a man of many parts that no single individual comment or testimony can exhaustively cover.

Though it is said that no man is perfect, LKJ excelled in virtually every area of life he impacted. From journalism (as a practitioner and administrator) to politics and governance (first, as Executive Governor of Lagos State and later, as Minister of Works), he was first class. He left indelible footprints on the sand of time. Indeed, so huge are his footprints that many generations to come will struggle to match.

In all these areas, he distinguished himself as a man of great ideas and seriousness of purpose but not effusive. He was a man of many parts: a devout Muslim who respected the religion of others, a mass social mobilizer, and an amiable, considerate, kind and compassionate leader to his followers, associates and millions of admirers around the world.

That is generally speaking. Now, to the chore of this article; which is my personal experience under the shadows of the great journalist and the diverse ways he positively impacted my life. There is no way I would narrate this experience without telling a part of my life’s story.

It all began 49 years ago, after my two-year Higher School Certificate program at the famous Ilesa Grammar School, Ilesa, now in Osun State. I had worked briefly as a sorter at the Ibadan Post office and followed it up with a one-year stint as a teacher at Molusi College, Ijebu Igbo, now in Ogun State. I returned to Ibadan to live in the house of Chief Gabriel Akin-Deko, my uncle; still thinking of what to do with my life.

Then, fortuitously, in January 1972, my bosom friend, Eric Teniola, then a cub reporter with the Nigerian Tribune, talked me into applying to the newspaper as a cub reporter. I did, and two days later, I got an appointment letter to start work on 2 February, 1972.

I resumed as early as 8 a.m. dressed smartly in one of the few shirts I owned. At 10 a.m., a black Peugeot 404 salon car drove into the one-storey building housing the Nigerian Tribune offices situated at Adeoyo Road, a few meters from the famous Adeoyo Hospital, Ibadan. The stairs and the upper floor of the storey building were made of wood. Solid wood.

I did not see the occupants of the black car but heard footsteps moving into one of the rooms. Some minutes later, the editor of the newspaper, late Ikhan Yakubu, walked in and met me in the newsroom. He walked into his office, beckoning me to follow. He had an intimidating huge frame. He sat down and asked, “You are the new cub reporter?”

“Yes sir”, I replied.

He nodded and told me a few things. Then, he rose up suddenly and asked me to follow him. I did. He walked me into an office where I met someone in simple Buba and Sokoto native attire. I would later discover that simple style of dressing to be part of the man’s signature.

My editor introduced me, saying: “Young man, this is our boss, the Managing Director of this company.”

I prostrated to greet him.

“What’s your name?” he asked me, his face expressionless. I did not hear what he said. So, he repeated the line: “What is your name?”

“Lawrence Mofoluwaso Olamiti,” I stammered.

“I will call you by your first name, Lawrence,” he said, his face still dead pan.

The man talking to me was none other than the great Alhaji Lateef Kayode Jakande, Managing Director of the Nigerian Tribune; my Managing Director.

Though a little rattled and intimidated standing in front of this man with expressionless face, still meeting the man for the first time gave me an inner joy, an unquantifiable peace. Then the man peered from behind his thick-rimmed glasses and asked my editor, Ikhan Yakubu, to excuse us.

Now, face to face with Alhaji Lateef Kayode Jakande, I noticed a wry smile playing on his lips. I couldn’t decipher whether he was smiling or sending me a message. Suddenly, he flipped out a ten kobo coin and said, “Go and buy booli (roasted plantain with groundnut).”

“But I am not hungry, sir,” I said most respectfully without looking at him.

He did not answer me. Rather, he started writing. Suddenly, he intoned: “They are for me.”

As I prepared to storm out of his office to go and buy the local snacks across the road, he said in a soft voice: “We are eating together.”

Eating together with my MD? Eating together with the great Jakande? I wasn’t sure I heard him right. I was momentarily paralyzed with fear. But the fear evaporated as soon as I saw him devouring what he described as his breakfast at 3.20 p.m.

After doing justice to the booli and groundnuts, he cleared his throat and told me to sit down. And he began to lecture me on how to become a crack reporter.

“For you to showcase yourself as a successful journalist, you must dream it, think it, and romance it. A serious-minded journalist does not go hungry, and neither does he have appetite for food. What we have just taken with a bottle of coke is to energize us,” he lectured me. From that day on, Papa Jakande developed deep interest in me, and a deep symbiotic relationship began between father and son, with my journalistic father calling me Lawrence, my baptismal name, from that day.

The next day was eventful. Pa Jakande arrived from Lagos around 1 p.m. He got a call from somewhere that the University College Hospital (UCH), Ibadan, was ‘boiling’ as workers went on strike and had trooped out in large numbers to demonstrate with placards clamoring for the removal of the Chief Medical Director (CMD), Mr. Cole.

Immediately, the MD called the editor and asked him to assign me to cover the event. I went in the company of my dear late friend, photojournalist Dada Osasona, on his scooter. I kept wondering why my MD would assign a green-horn reporter like me to cover a demonstration of that sort.

All the same, we went to UCH and came back to write what I observed. I did my best, dotting the i’s and crossing the t’s. I took my story to the editor; he did not even look at it. Rather, he directed me to LKJ’s office. I knocked and entered. He was still writing. In those days, there were no typewriters allocated to any of the journalists in the newsroom to type his story. We wrote our stories in a long hand and gave them to the typist attached to the newsroom; who would knock the handwritten stories for us.

I stood before Alhaji Jakande for close to an hour. He never lifted up his head to acknowledge my presence. When he was done with his writing, which I later discovered was the editorial comment for the next day, he handed the copy to me for onward transmission to the typist. Then, he began to read my story. Once a quick glance at the stuff, he lowered his glasses and looked directly into my eyes.

My heart raced. ‘What is it now,’ I asked in my mind. I don’t know whether he saw my expression or not. But he gave me a second look, then suddenly, he said, with a wry smile:

“You have just written a composition good for a school essay,” he said. Thus, I began my second lecture for the day. He took the pains to teach me how to structure a news story. He tore what I had written into pieces and told me to go and re-write it while waiting for the picture. In a nutshell, I re-wrote the story five times. Finally, he okayed it after many amendments with his green pen.

When the picture landed on his table, he sent for me. He showed me one of the pictures where he saw me holding one of the posters with the inscription “Cole Must Go”. LKJ asked me what I was doing with the poster.

“I was engrossed with the protest. In my excitement, I did not know how I got one of the posters and joined in shouting “Cole Must Go”. I replied sheepishly.

LKJ burst into laughter. I never saw him laugh so heartily. He told me afterward that “a good reporter never gets himself involved in an event he goes to cover. You dissociate yourself from it to get an unbiased story.”

When he felt satisfied with my story, he gave me some money to buy roasted plantains, groundnuts, and coke. From that day on, I improved on my writing skills, and he was satisfied with my rapid progress.

LKJ picked special interest in me as he recommended me for a three-month reporting course at the newly established Nigerian Institute of Journalism at Apogbon on Lagos Island in November 1972. I was barely five months on the job as a cub reporter. I did well in the course. I passed with distinction. Upon my resumption of work at Ibadan, I got a pleasant surprise. I was promoted to the post of News Editor to succeed. Mr. Fola Oredoyin.

A few days after my promotion, I got a message from LKJ from Lagos directing me to get ready for an assignment in Ile-Ife. It was a special lecture to be delivered by Chief Obafemi Awolowo at the then University of Ife, Ile-Ife. I got to the office as early as 6 a.m. My MD drove in at 6.30 a.m. from Lagos. Pronto, we were on our way to Ile-Ife. We rode in his popular black 404 Peugeot.

The event went well. On our way back to Ibadan, not quite five kilometers from Ile-Ife, LKJ coughed as if he wanted to clear his throat. “Have you written your story?” he asked me.

“No sir”, I answered, “I will do so when we get to the office.”

Again, he began to lecture me on how to write good stories without notes. “First,” he said, “the salient part of the lecture would form the introduction to build a solid structure for the story.”

Then, he started dictating the intro and the rest of the story to me to write while he was driving. Amazingly, I got the byline for the first-class story I did not write. It was a priceless gift of journalism lesson I could not get from the classroom that LKJ gave me.

LKJ gave the Nigerian Tribune its unique character as a fearless tabloid to date. The powerful editorial comments of the newspaper from the era of Papa Awolowo/Akintola political feud in the old Western Region to the periods of Nigeria’s military regimes, to the Awo/Shagari era of the Second Republic, back to military rule in those days, came from LKJ’s arsenal. Some of the editorials landed me in detention in the then Nigeria Security Organisation (NSO) gulag at Awolowo Road, Ikoyi, Lagos.

I remember the day the Federal Military Government came out with one of their unpopular policies. We got the news at 5 p.m. at our wooden one-storey building along Adeoyo Road, Ibadan. LKJ was about leaving for Lagos. He decided that a no-holds-barred editorial should be written for the next day’s edition of the Nigerian Tribune. He was racing against time. He beckoned me to come with him but demanded to ride in my Volkswagen Beatle while his driver would drive his car behind us. I remember his son, Tunde, was in the Peugeot.

LKJ took over the wheel and asked me to start writing as he dictated the editorial. It was a laborious exercise as we had to navigate through the uncompleted Lagos-Ibadan expressway back to the old road. He finished dictating the comment within one hour, by which time we had arrived in Ijebu Ode.

He stopped and asked me to read it to him. I did, and he made a few corrections. He patted me on the back, and I drove back to Ibadan. I got to the office at about 9 p.m. The earth-shaking editorial was published on the front page the following day. Back then, hot metal was the technology used for the type-setting before printing.

LKJ was deeply interested in my capacity development. He soon organized another training for me. He arranged for me to attend a two-year course at the Nigerian Institute of Journalism, NIJ, Ogba, Lagos. That was in 1974, and my set was the second. Initially, I told him I had no money for the course as my meager salary was not enough to take care of myself and my poor family. My father, a catechist, was serving God virtually without salary. LKJ assured me of his support and gave me study leave with my monthly salary paid all through the period of the course.

A year later, he recommended me for the prestigious Thompson Foundation Senior Editorial Institute in Wales, England. I was also on study leave with my full salary paid. I also trained at the School of Journalism in Germany.

God used my boss, LKJ, to help me build a successful career in journalism. Most of what I have achieved to date, by the grace of God, is traceable to my professional practice under LKJ. He saw to my welfare while with the Nigerian Tribune and after. As far as journalism is concerned, he was my Guardian Angel. He was always there for me. He gave me a lifeline at a time I needed it most. His impact in my life is immeasurable.

In his active days, LKJ always had a serious, though calm, expression on his face, which made many fear him. But beneath this facial expression was a good heart, full of compassion and milk of human kindness. For many of us who worked closely with him, our experience of him was that of a leader who sought the welfare of his employees and extended a helping hand before they could even ask.

May his great soul rest eternally in perfect peace. Adieu, Boss and great mentor.

Folu Olamiti Media Consultant writes from Abuja.